|

Arctostaphylos and Ceanothus are probably the two most popular genera of native ornamental shrubs in the Far West. Their preference for dry summers, poor soils, and their all-around toughness make them well suited to our region; and they reward the gardener with form, leaves, and floral display of unique appeal.

While the popular garden hybrids of Arctostaphylos and Ceanothus generally originate from California and Oregon, these genera are surprisingly well represented to Washington State. I've written this article to describe all the native species I am aware of, and highlight some of their virtues and potential as garden ornamentals.

Arctostaphylos

Arctostaphylos uva-ursi hanging from a roadcut in the

Olympic Mountains, Washington.

|

Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (Kinnikkinnik) is the best known species in the genus and is even familiar to many non-gardeners. A modest but appealing plant, it is native to much of the Northern Hemisphere far beyond just the west. Usually forming a low mat of green leaves, it trails along the ground to a height of about 6". Little white bell-like flowers in spring are followed by red berries in late summer. In Washington it is quite common in the western Cascade foothills, and along the east slopes of the Olympic Mountains, and it may be found in many other areas. In the Northwest, selected forms such as 'Vancouver Jade' and 'Massachusetts' are popularly found in nurseries: these are very widely used as groundcovers in both residential and commercial plantings. For something more interesting, pursue 'Wood's Dwarf' (Wood's Compact'), a diminutive form with tiny leaves and loaded with berries, or 'Point Reyes' and 'Alaska', which have wider, more rounded leaves.

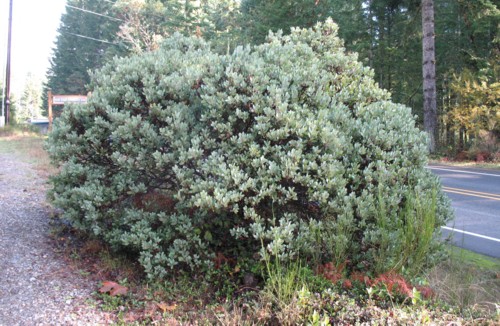

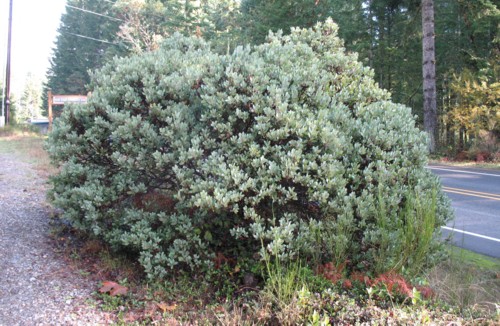

Arctostaphylos columbiana in Hoodsport, Washington.

|

Arctostaphylos columbiana (Hairy Manzanita) is the most familiar shrubby species native to Washington. An impressive plant frequently growing to 10' tall or more with greater spread, it has the same smooth, mahogany-colored trunks and contorted habit as the familiar California species. Leaf color is usually blue-green with some forms bluer than others, and tending to look greener in winter. The flowers are showy clusters of white bells, which are followed by deep red (rarely yellow) berries in summer. In Washington, it is rare in much of the immediate Puget Sound area, but rather common on the Kitsap Peninsula, on the east foothills of the Olympic Mountains (as high as 4,500'), and in the San Juan Islands. It is less frequent in the Cascade foothills, but becomes more common southward towards the Columbia River Gorge, and it may be found as high as 5,000' near Mount Rainier. It also occurs southward into Oregon, and north into the Gulf Islands of British Columbia.

Leaves and upripe fruit of Acrtostaphylos columbiana on

the Kitsap Peninsula,

Washington.

|

It is usually found in clearings in the forest where at least ½ day of sun can get in, often colonizing disturbed areas. In the garden, hairy manzanita is not difficult to grow in a mostly sunny position with very good drainage and no supplemental water. It remains uncommon in cultivation, probably because its nursery production requirements differ from the standard heavy-watering regime used for most plants. Although native, it can be rather susceptible to fungal leaf spots: superior resistant forms should be selected.

Arctostaphylos nevadensis (Pinemat Manzanita) is often compared with A. uva-ursi, but it is clearly distinct: it is not as dense, the leaves are more pointed, and although it is a low plant, it might not be considered a true groundcover, as it often (but not always) hovers just a little bit off the ground. The leaves are green to green-grey (most forms in Washington are more on the green-grey side) and less glossy than those of A. uva-ursi. It is an attractive plant as the open habit makes the peeling red-brown bark and angular branch pattern more visible.

Arctostaphylos nevadensis near Mt. Stuart, Washington.

|

In Washington it occurs primarily along the east slope of the Cascade Mountains, in rocky fells and under the pine trees, preferring very dry and well-drained conditions. Its range extends at least as far north as the north end of Lake Chelan, and it is very common in the Mount Adams area. Near Mt. Stuart it occurs as high as 5,500' but it also occurs as low as 1,000' in some places. It also ranges southward into Oregon and into northwestern Nevada. In the garden it remains an uncommon subject and has a reputation for being difficult to establish. In rainy areas it is best suited to a rock garden with excellent drainage and surrounded by large rocks, but with a cool root run. Superior selections of this species are certainly worth the effort.

Arctostaphylos patula, Natural Bridges National

Monument, Utah.

|

Arctostaphylos patula (Greenleaf Manzanita) is an impressive shrub of variable size and stature, all forms having deep, lustrous green leaves in common. It has the same beautiful smooth, red bark as the popular species and white flowers that may occur in large clusters in some forms. Although widespread across the interior West as far south as Arizona and eastward to central Colorado, it is the least common Arctostaphylos species found in Washington. It is known primarily from Klickitat County in the Glenwood area and along the shores of the northern part of Lake Chelan. Plants in the Lake Chelan area have been reported to grow as tall as 15', but the author cannot confirm this. This species is undeservedely rare in cultivation, as it would make a stunning specimen. It seldom has disease afflictions and ought to be quite easy to grow once established, in a very dry, gravelly spot in the garden.

Arctostaphylos x media in one of its many forms, seen

here on the Kitsap

Peninsula, Washington.

|

Arctostaphylos x media is the name applied to hybrids of A. uva-ursi and A. columbiana. These vary considerably in size and form, and occur on a number of sites around western Washington where the two species are found growing in proximity. Some of these forms make excellent garden plants and are not difficult to grow. Although this hybrid has been known about for many years, none of its forms seem to have really 'caught on' in cultivation yet. The author hopes that more of these plants will be selected and trialed for garden-worthiness in the future.

Arctostaphylos patula x A. nevadensis is found in the few locales of Washington that A. patula occurs, as far as the author can gather. In some areas these hybrids are reportedly so common that it is hard to find a pure A. patula. With fresh green leaves and vigorous, spreading growth; these plants are very appealing as ornamentals and have great potential. I believe Colvos Creek Nursery may be introducing some of these to cultivation in 2008.

Arctostaphylos patula x A. nevadensis in Stehekin,

Washington.

|

Arctostaphylos patula x A. uva-ursi may also occur in the Lake Chelan area. The parent of some plants observed is obviously A. patula, but the author cannot confirm whether the other parent is A. uva-ursi or A. nevadensis.

Arctostaphylos columbiana x A. nevadensis is known from the Big Lava Bed area of the South Cascades, where it was found in the 1970's by esteemed plantsman Arthur Kruckeburg. The author has not seen these plants but some forms might be selected and trialed as interesting garden subjects.

Arctostaphylos columbiana x A. patula may someday be located in the Bingen or Willard area, if both species can be found growing together. As yet the author is only aware of this hybrid occurring in Oregon.

Ceanothus

Ceanothus velutiuns flowering in September in the Wallowa

Mountains, Oregon

|

Ceanothus velutinus (Snowbrush) is perhaps the most prominent species of Ceanothus native to Washington. A sturdy, spreading plant of rather open habit, it usually matures at about 4' tall and 7' wide or so. The leaves are rather large for a Ceanothus (about 2" broad), glossy dark green, and viscous. Upright panicles of showy white flowers are produced in early summer. Snowbrush is frequent on drier mountain foothills and slopes, from the east slope of the Cascades to the Satus Pass area and over to the Blue Mountains, as well as in the northeast corner of the State. It also occurs southward into California, eastward into the Rocky Mountains and north into British Columbia. It prefers to inhabit dry areas with poor, often rocky soil and may be found in avalanche tracks or colonizing disturbed areas. In cultivation it is a valuable broadleaf evergreen plant that is too frequently overlooked as a potential garden subject. The showy white flowers and large glossy leaves are both appealing. Probably the main reason it is rare is that it is rather difficult to propagate.

Ceanothus velutiuns var. hookeri, cultivated in Poulsbo,

Washington. This plant was

a volunteer seedling that a gardener on Bainbridge

Island didn't want.

|

Ceanothus velutinus var. hookeri (formerly known as C. velutinus var. laevigatus) is essentially a treelike, maritime form of the preceding species. It has essentially the same features, but may grow as tall as 15' (rarely 25') on a plant of rather open, gawky appearance. Native to low to moderate elevations western Washington, it is more common west of Puget Sound, often growing with Arctostaphylos columbiana and Pinus contorta var. latifolia, but occasionally found in the shade of large Pseudotsuga menziesii and Pinus monticola trees. In cultivation, it grows very well with decent drainage (gravelly soil not being as essential for this one) and complete neglect. In gardens it could easily be trained to have an appealing shape, though its natural form is not unsuitable for a wild-looking garden. The flowers are very showy on even larger panicles than those of the species, but they may not bloom every year! It is very rare, probably because of the difficulty in propagating it. This species has excellent potential for hybridization, and is the parent of at least one garden-worthy natural hybrid, C. x mendocinoensis (C. velutinus x C. thrysiflorus) from California.

Ceanothus integerrimus (Deerbrush) is a large shrub to 8' and as wide. The leaves are softer than those of many Ceanothus species, and are frequently browsed by deer in the wild, an occurrence which it seems to take in stride. It varies from white to blue (rarely pink) in flower color, and from evergreen to deciduous, having a large native range south to Mexico of which Washington is but the northernmost extension. Forms from the north (including Washington) tend to be more deciduous in habit, but on the positive side Washington has some forms with the best deep blue flower color. In Washington it is restricted to the southern part of the state from the Mt. Adams area over to Goldendale. An appealing garden plant with an exceptionally airy look, it may occasionally produce showy flowers at other times of the year besides the main display in spring. Although rare, it is not a difficult garden subject and moderately easy to propagate from cuttings.

Ceanothus prostratus near Klamath Falls, Oregon.

|

Ceanothus prostratus (Mahala Mat) is, as the name suggests, a prostrate species that grows no more than 6" tall. Its neat, dense, impenetrable mats of foliage are decorated with blue to indigo flowers in the spring. As with C. integerrimus, it has a large range throughout the West, barely extending into Washington in Klickitat County, where it is common. It has also been reported from a single occurrence in Chelan County. It generally prefers dry, south facing slopes in open forest or clearings, never far away from Pinus ponderosa and usually some species of Arctostaphylos. Mahala Mat, despite its appeal as an ornamental, is extremely rare in cultivation. It has a reputation for being next to impossible to grow in gardens, but perhaps one could be successful by mimicking the conditions found in its native habitat. It is very easily propagated from cuttings.

Ceanothus sanguineus (Redstem Ceanothus) is a deciduous shrub that may reach 8' tall and wide. Its glossy green leaves are attractive, but the white flowers are not as showy as those of other species. Native throughout most of the state of Washington except for desert areas, it is always appealing but never conspicuous. Rather easy to propagate, native plant specialists often carry this species. It has less in common visually with the California species of Ceanothus, but it is probably the easiest Washington native Ceanothus to find and grow in gardens.

The author has not heard of any of our native species of Ceanothus producing natural hybrids in Washington State, but of course, this possibility can't be ruled out. Hybrids of our native Ceanothus species could result in excellent ornamental garden plants.

This concludes my summary of Washington's native Arctostaphylos and Ceanothus. Hopefully your low-water-use garden can provide a home for at least some of them - and hopefully you can find the plants!

Back to Articles |

Home

|